Writing in the ChatGPT Era

The second essay in our series on humanity at the dawn of the era of artificial intelligence.

In the month of March, we’re bringing you essays on humans, machines, and artificial intelligence. These essays span the spectrum of viewpoints—from techno-optimism, to techno-skepticism, and something in-between. In the first, I wrote about what it means to be human in the age of AI. This week’s guest essayist bridges the gap between AI/ML and Art—as a writer and as a product manager for an AI startup.

I was a late bloomer when it came to reading and writing. My preschool and kindergarten education was a jambalaya of Waldorf, Montessori, and other new-agey pedagogies commonly found in Boulder, Colorado, in the 1990s. Those years gave me a wonderful exposure to folklore, fairy tales, and basic morality, but not literacy. I remember seeing some of my elementary school classmates reading “chapter books” — rudimentary literature — while I was still stuck on picture books, sounding out every letter and syllable of each word.

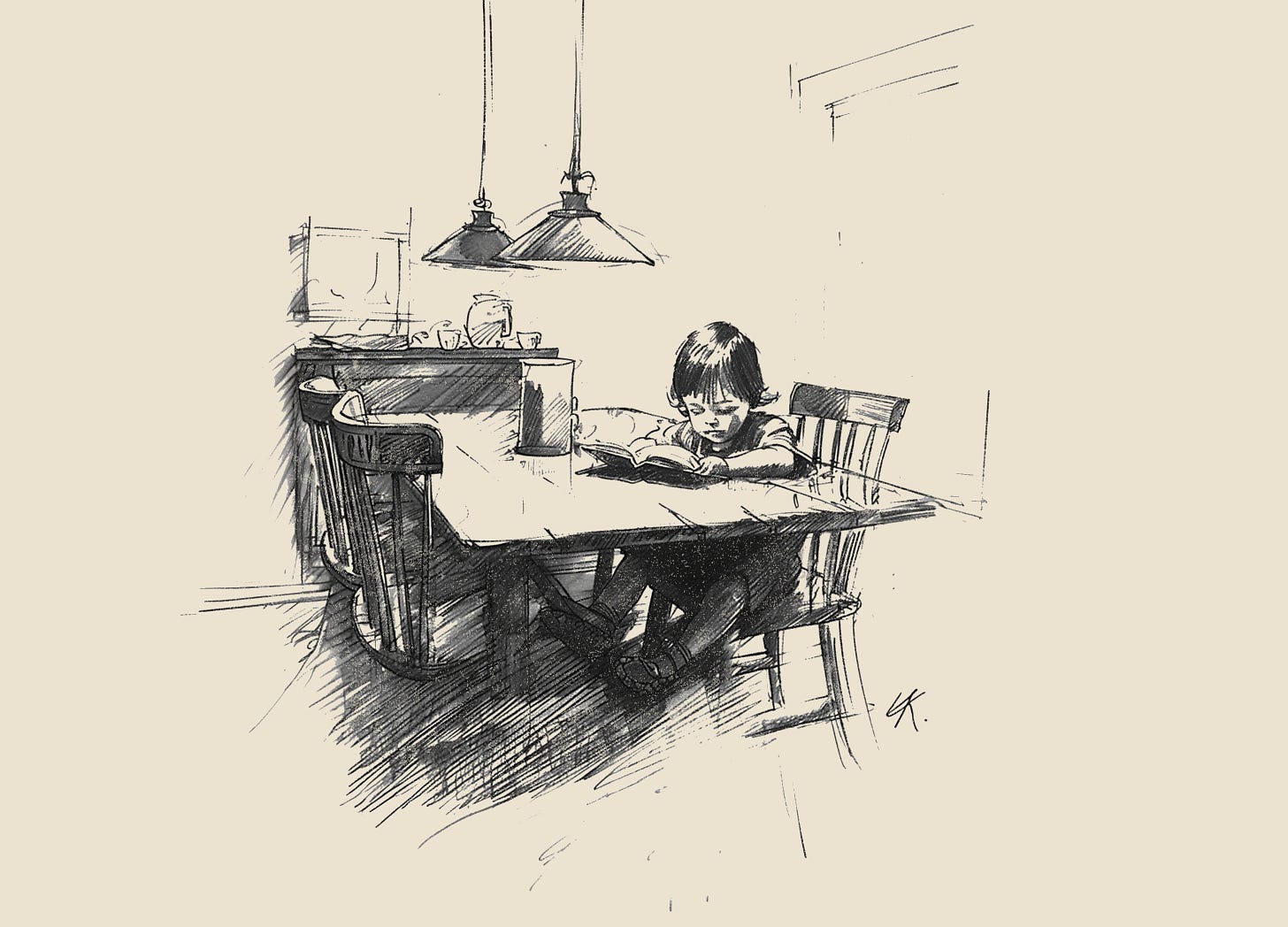

Then, halfway through the second grade, I discovered Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone. I read the whole book over a weekend. I remember sitting at the kitchen table with the paperback and a bowl of bean soup, which I didn’t touch until long after it became desiccated sludge. I remember finishing the book and feeling that I had stepped into a whole new world; not only the world of Hogwarts and Harry, Ron, and Hermione, but one where I could read well — where I could read anything. I felt proud. I knew then that reading was a very good thing for me, possibly the best thing that any person could do to gain both knowledge and cognitive stimulus, and for immersion, for escape from the drudgery and murkiness of the real world.

The Hobbit, still one of my favorite books today, came next. The rest of elementary and middle school was filled with trips to the public library and local bookstores. I devoured the Redwall series, Ender’s Game, The Lord of the Rings and the Silmarillion, and so many others. I remember wandering into an empty room during a lightly supervised Unitarian church Sunday school session and reading half of the New Testament. My next door neighbor and best friend was a dual citizen of the United States and Finland, and so I found myself poring over a detailed history of the Soviet-Finnish Winter War.

The next phase began with Christopher Paolini and his precocious Eragon. It’s a fine fantasy novel in its own right, but what astounded me at the time was that he had published it at 19. I was 12 — I had near-endless time to match or beat his achievement. I could become a professional author. I could build worlds for others to revel in, and doubtless make good money doing it (to be spent primarily on soda, candy, pastries, and other prestige goods). This all seemed like the most natural and obvious thing in the world to someone who loved reading more than most things.

I did not do any of that.

I did manage to write a transliteration of The Hobbit as a middle school play, with extraordinary support from one of my teachers. I jotted down a few dozen pages of an abortive fantasy novel. And that was it. High school, teenage romance, and video games took over from there. My reading plummeted to a slow drip with fleeting storms – A Song of Ice and Fire. I went to college, and I didn’t study writing or English. I studied abroad. I joined the Marine Corps. I met my life partner, and got married. I eked out a few articles on politics and policy, about one per year.

And I quietly held on to my childhood fantasy of writing fiction for a living. The personal ethic that came to me, in large part from my foreign travels and military service, told me that reading and writing were part of what I was meant to do. I believed that they were good for me, that I was good at them, that they were good for humanity. As Dr. Robert Doback might put it, I always held on to my dream of becoming a dinosaur.

Eventually, with active duty, graduate school, and other excuses for not writing behind me, I got a grip. I went for it. For me, this meant writing a few short stories set in a fantasy universe I’d been building in my head for the past decade. Today, this amounts to something like fifteen thousand words. It’s not much right now, but I’m as happy and proud of these scribbles as I was at age 7 when I finished that first Harry Potter book. I can see a horizon where I’ve produced some original body of fiction, one that other people may even enjoy. Hooray!

But there’s something uneasy here. When I carve out time to write, I feel like a pendulum shearing back and forth between doubt and faith in what I’m setting out to do. I spend a lot of time thinking about futility, and meaning, and the meaning of meaning. What it means to write, to seek originality, and to create in the world of ChatGPT and generative artificial intelligence.

To recap for the layperson, ChatGPT and other Large Language Models (LLMs) are algorithms that can predict, analyze, and synthesize all manner of data – text, imagery, audio, video – not just quantitatively, but conceptually. These LLMs use deep neural networks, reinforcement learning, and knowledge graphs to build probabilistic models of the relationships between individual data elements, and to then make accurate predictions or renditions derived from that “training” data in response to new “inference” data inputs (i.e. human-generated prompts).

I should mention here that I work for an AI startup. I’m not a Luddite, in the contemporary sense; the historical Luddite movement was a protest against unjust and immoral labor practices during industrialization, not technology itself. I am immersed in this community of exploration and disruption; I celebrate its successes and silver linings. I enjoy tinkering around with chatbots and image generators. I spend a lot of time honing my technical knowledge so I can be an informed practitioner and observer in this space.

This is what I fear: the writer’s craft is under threat. Cheapened. Exploited. Irrelevant? Every story of personal and corporate glee at all of the ways that LLMs can make and save money or time feels like a velvet dagger to me. We’ve already weathered a decade of social media, where the quality of media content, critical thinking, and public discourse has been degraded to unfathomable depths. The business models available for professional writers and artists to make a living wage are on life support. Most concerning of all — the most promising and profitable generative AI models are built on a foundation of questionably acquired intellectual property.

And so I ask myself, why should anyone today try to create an original work of art, writing, or philosophy? If we all come to rely on LLMs and generative AI for creativity and originality, what are we sacrificing? Will anyone be able to make a living as a full-time creator in 10 years? If not, what does that do to our culture? Is anyone else as bored by this era of images that are always dazzling, but also predictable and generic? The tidy essays that are just vague pulp screeds of text? The overarching question of artificial intelligence and its development towards Artificial General Intelligence (AGI, or human-level machine intelligence) is so sweeping that it quickly fractures into existential debates on the future of our society, economy, and the meaning of life itself. Not all possible futures in those debates are good for most humans.

Personally, I do not believe that LLMs are a genie released from its bottle. It’s not that simple. Any technology, any artifact, is political; humans always decide collectively how to build it, how to use it, who has access to it, who benefits from it. It’s just as lazy for us to throw up our hands and accept some type of haphazard utopia-dystopia as it is for us to bury our heads in the sand about the inevitability of technology-driven change. There are all types of legal, policy, technical, and moral solutions to help us shape the future we want to live in. Creators and media companies are fighting for their intellectual property rights in court. Civil society and elected officials are devising new ways to mitigate the negative externalities created by LLMs and automation generally. There’s a better equilibrium waiting for us, if we can manifest it.

But let’s return to world building. To write fiction is to build a world for everyone, anyone to revel in and enjoy. What happens when that world is pillaged for commercial gain? What kind of world are we building with LLMs here, now, today — on Earth? Who is this world for? These are questions for humans, not chatbots .

I’ll leave you with one more of my favorite worlds, the Expanse universe by Daniel Abraham and Ty Franck. It’s a vision of our world set several hundred years into the future, one where humanity has mastered space travel and colonized the solar system. In The Expanse, there is an entity called the “protomolecule.” It usually manifests as a glowing blue slime that saturates and changes everything it touches – biology, chemistry, and physics. It’s a powerful force that constantly alters the world around it in unpredictable and often devastating ways. Every faction in the universe tries to control it for their own purposes. It’s not morally good or bad – the protomolecule is explosive change. It’s a brilliant umbrella metaphor for technology.

For any writer or artist, now is a time to dig deep for meaning and purpose. Why do I choose to write? Everyone must answer this question for themselves, and I want to leave many possible answers unwritten here. For me, the very first and most important reason to write is that writing is an act of creation. It’s a place to begin — to rethink our relationship with technology, with other people, with this planet that sustains all known life. And we desperately need all of those things in this world, the real world. Writing is hope. The fact that we can still think, write, and compete without the Promethean fire of some proprietary corporate platform is simply a wonderful and hopeful thing. And I’ll be happy as long as I can keep scribbling.

I might even learn to draw.

Enjoy essays like this one? Consider subscribing.

The Portmanteau—essays and social commentary for everyone, even level-headed, curious, thoughtful people.