Thoughts on Singleness in a World of Relationships

Our society believes in two states of being—you're either in a relationship or trying to find one.

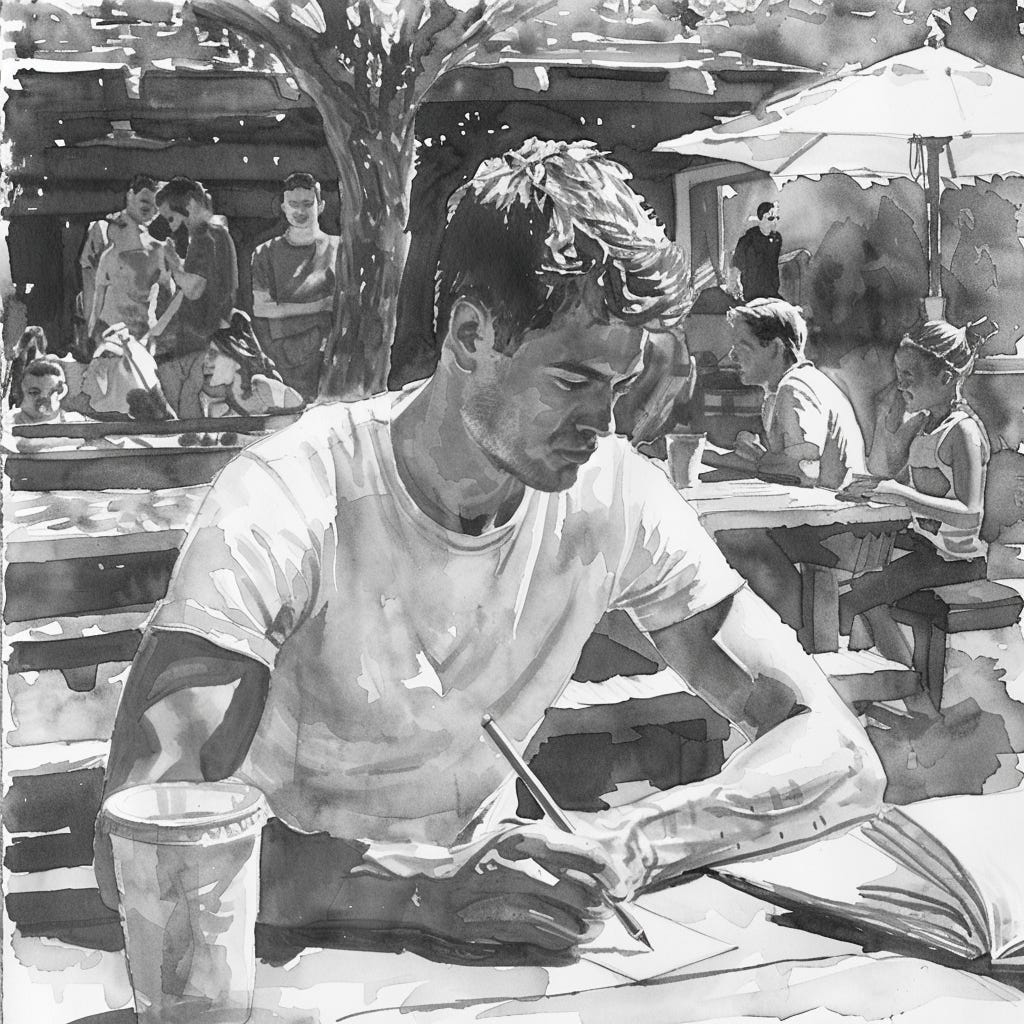

On Sunday morning I sat on the patio of my neighborhood coffee shop sipping black coffee and eating a breakfast sandwich—everything bagel, cheese, sausage. It was early, and local patrons wandered in and out, most not staying, instead beating hasty retreats back to their homes, coffee in hand, in various states of early-Sunday-morning-undress. A woman sat on the patio near the playground talking to her toddler in French, who smiled pleasantly and tottered unsteadily around the picnic table. A lone man with two handsome German Shorthaired Pointers sat on the porch, scrolling on his phone. A couple pushing a stroller disappeared inside. They reappeared a few minutes later holding iced lattes, parking themselves at a picnic table. I instantly liked them.

Eventually, couples appeared from everywhere, carrying children, pushing children in strollers, in carts, carrying them in backpacks. I think I even saw one toddler pulled from a FedEx box. The patio and playground were swarming with toddlers under the age of five while parents looked on watchfully, carrying friendly conversations with one another. Funnily enough, I liked all of them as well. I trusted them, these couples I didn’t know with their strollers and buggies who had quickly transformed my quiet writing time into a joyful coffeehouse bedlam. But what did these people think of me? A single 32-year-old man sitting by himself?

Our society believes in two states of being: in a relationship or trying to find one. To fall outside these two states is to announce yourself as a social pariah. This dichotomy is further accentuated by marriage, and we view people who aren’t married as completing a triple crown of failures—social, biological, and patriotic.

First, social. We tend to trust people more readily when they have a spouse or partner. That trust extends down even to the potentially more transient instance of boyfriend or girlfriend. Maybe it’s an evolutionary development that signals I’m not a psychopath, see, I have a steady relationship.

I’m not free from this bias, either. At one company I worked for we hired a new CFO. When introducing himself to the crowd of in-person and virtual employees he showed us pictures—of his dog. He made no mention of a wife, much less any family. It unleashed a flood of suspicious questions in me. He’s in his mid-fifties. Why didn’t he mention his family? Is he divorced? Why is he divorced? Where are his kids? If he has any? What’s wrong with him? Can he not keep a relationship? Is he gay? While I might have rolled my eyes when our other new executives put yet another photo of their family on the screen, I could only accuse them of being blasé but not of untrustworthiness.

Like most people I use marriage and relationships as a simple trust heuristic, and I naturally tend to trust a married person faster than a single person, marriage being the proxy for a host of other things like commitment and stability. Oh, if someone trusts you enough to marry you then maybe I can trust you, too, we think. Watch any politician running for office. Watch an ad for their campaign or a political speech they give. They’ll often trot their family out on stage afterward, a not-so-subtle virtue signal: “I’m married. You can trust me.”

The second failure is biological. For men there seems to be a general level of tolerance for a mid-30s bachelor, but twin pressures emerge for women from society and biology. If they want kids of their own, then ‘the biological clock is ticking’ as they’re too often told by friends, family, advertisements, and their own monthly period.

The final failure is patriotic. A friend of mine recently compared the declining populations of Japan and South Korea to a similar trend happening in the United States, stating that he felt a responsibility to contribute to the replacement rate. I’ve heard similar arguments before, and there’s some truth to them. Japan’s drastically low birth rate of 1.26 children for every woman has induced panic in the country, forcing the Prime Minister to state that reversing this ‘depopulation’ is a top policy priority. A population with an older average age and declining births creates the economic conditions for catastrophe as there will be no working age people to support the country, pay into the social welfare system, generate new ideas, start new companies, etc etc. South Korea is facing a similar, though not quite as dire, situation. The United States may be headed the same direction.

Our culture is obsessed with marriage, or at least relationships, and I’m not arguing that this is a bad thing. Marriage includes all sorts of benefits—in men it's correlated with higher income, longevity, and increased happiness. It’s a code that economists have been trying to crack for decades: what is it, exactly, about marriage that makes people more successful? Happier? Healthier?

According to The Knot, in 2023, the average age for women getting married in the US was 28.6 and for men was 30.5. This is much higher than 70 years ago. The median age in the 1950s was 20 and 23 for women and men, respectively, but that doesn’t change the truth that now, if you pass these median ages you turn a mirror on yourself and ask, “Is something wrong with me?” One of the questions I’m asked most commonly is “Are you dating anyone?” implying an expectation that I should be dating someone. Also implied is a subtle judgment if I happen to answer in the negative.

Study after study, in publications as diverse as The Atlantic and the City Journal affirm that married people (especially men) are indeed happier. City Journal lists 10 reasons for this, which range from increased sanity to increased savings. In The Atlantic Olga Khazan writes that overall happiness in the US has decreased since 2000. Many believe the culprit to be the declining marriage rates. In 2002, the Fed of St. Louis tried to understand why men who marry make more money (11% more on average) than those who remain single—or those who get divorced.

In the midst of this, those of us who pass the average marriage age tend to feel a little bit like freaks. And I imagine it’s only worse for women than for men, something my single female friends confirm.

Get married! We’re told. You’ll have better sex! You’ll be richer! You’ll be happier!

To fall between the in-a-relationship or on-your-way-to-one states-of-being is to invite social reprobation.

Others might argue that – like married life – foregoing marriage brings with it a number of singular advantages. Most often these revolve around time, discretion, and agency without encumbrance. But when my married friends make offhand comments about living vicariously through me or express hints of envy at what they interpret as a less entangled life, they’re missing something important about the basic economics of both time and money. Being single doesn’t provide you with more free time. As both the Fed of St. Louis and City Journal rightly point out, marriage allows for specialization, and that specialization allows for greater productivity and more available time. As City Journal puts it: “ . . . married households have twice the talent, twice the time, and twice the labor pool of singles.”

Consider this simple list of tasks and associated time to complete them:

Vacuum and mop the floors (1 hour)

Pull weeds (1 hour)

Grocery shopping (1 hour)

Cook dinner (1 hour)

There’s only one of me and none of these tasks can be completed simultaneously, so I complete them sequentially, taking up four hours in my day. A couple, on the other hand, has the advantage of running down these tasks in parallel: the vacuuming and grocery shopping, for example, can happen at the same time. As a unit, they can be in two places at once, completing the same amount of work in half the time.

A counterargument to this might be that a single person making enough money could outsource many of these tasks, thereby freeing up a similar amount of space in a schedule. But isn’t the same true of a couple? This further overlooks the important fact that married people tend to make more money through dual income, and they have added advantages in the tax code, giving them increased earnings on an annual basis.

Here’s what I mean in an overly simplified example: a single person living in Arkansas earning $120,000 and taking the standard deduction pays $23,689.91 in Federal income tax. Let’s say this single woman’s next door neighbors are a newly married couple both earning $60,000, so as a combined household they earn the same gross amount. However, the married couple has the option to file jointly or separately. If they file jointly, their income would be taxed as if it was $120,000. But if they file separately, the income is taxed at a lower rate, so they each pay $7,317.36 in Federal income tax for a total of $14,634.72—putting nearly $10,000 more back in their (combined) pocket. So not only do married people earn more but they also have the ability to maximize those earnings through the existing tax code.

Economic advantages, then, accrue to married couples in addition to the heightened social status and fulfillment of their perceived social and patriotic duties. Single people, I’m afraid, are outgunned, outspent, and literally outmanned (or womanned).

I often think about these social and economic advantages that accumulate for married people in relation to my own professional and social life. Is singleness a handicap in modern American society? Is it a handicap in my own life? Others, like Ms. Khazan, worry less about the economic benefits—she can’t, however, get around the added social standing. Although she questions the institution and utility of marriage itself, she concludes: “For me, getting married is more optical than emotional. I’m tired of being a woman pushing 40 who has a “boyfriend”.” At the end of the day, is it a social pressure that’s too immense to ignore?

My dad called me a few months ago. That wasn’t out of the ordinary. He and I have been in constant contact for a decade, when I graduated college and we started reading and discussing books together. It wasn’t out of the ordinary that the topic of conversation was indeed another book. What was out of the ordinary was his apology.

He had just finished reading a book about marriage—its goods, its bads, its utility and its ills. One of the defining points of the book was that our culture emphasizes marriage but that it isn’t for everyone. He called to tell me about the book and to apologize for the emphasis he placed on marriage in raising me. I was taught as a child that fulfillment as a human being was contingent upon marriage and children. He was now telling me that I was fulfilled just as I was. That I didn’t need something else to make me whole. That I was worthy.

The full impact of this conversation didn’t settle in for several weeks.

His words slowly tunneled their way into my soul and unlocked something buried there, some deep seated inadequacy and fear of inadequacy I had harbored much of my adult life. A burden I didn’t even know I had borne was released. I felt lighter, a lightness that freed up my mind to examine life with new perspective. Much of what I had done up to that point, I realized, had been an endeavor to prove my worth. The bright lights of my brothers with their broods of children and successful careers had always made my stumbling successes seem fainter in my eyes. In essence, I had always felt unworthy no matter the achievements, accolades, or worldly approbation.

Those conversations can’t be manufactured. We can’t ask all the dads in the world to call their daughters or sons and say that to them. For those of us who are single and lucky enough to hear it, however, it’s life changing.

The Portmanteau is a reader supported publication. Enjoy essays like this one? Consider subscribing or share with a friend.